Absorption – A Complete Guide

Absorption describes the rate and extent to which a substance, such as cannabis molecules

THC and

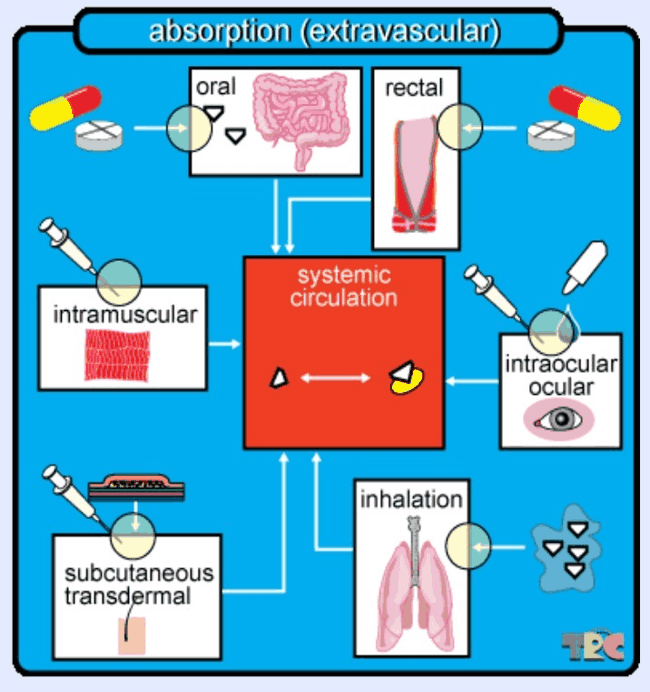

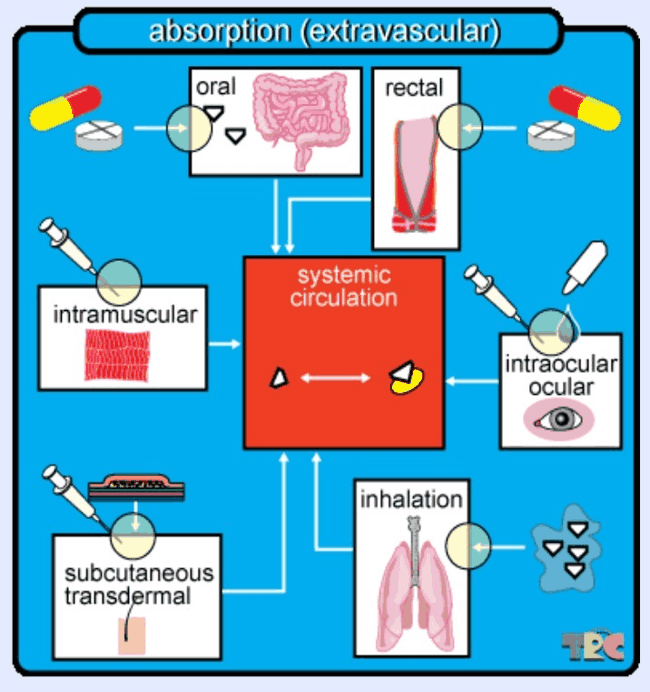

CBD, enter the bloodstream. Having a drug in your mouth may seem like it is in your body, but it needs to enter the blood first before it is considered absorbed. There are various ways for THC and CBD to enter the bloodstream, and each way has its own benefits and challenges. These ways, called administration methods, can be intravenous (drug injection directly into the vein) or extravascular (outside of the bloodstream), for example, administration via the mouth (oral), the mouth tissue (oromucosal), the skin (transdermal), the anus (rectal), inhalation via the lungs (intrapulmonary), etc. Understanding how much of a substance is absorbed into the body is important to understanding its effectiveness and safety.

1

In general, THC is almost instantly absorbed after inhalation, within minutes. In contrast, after oral ingestion, it can take up to an hour or more before a large amount of the THC is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract.

2, 3, 4, 5 The absorption of CBD is generally similar to the absorption of THC due to similar chemical properties.

6 We will get into more detail about this in the following sections.

Figure 1: If a drug is given by any other route than intravenously (directly into the bloodstream), it is considered extravascular and must therefore undergo absorption into the bloodstream. Here, the bloodstream is called the “systemic circulation” and is depicted in the center of the image. The various routes of administration depicted are oral, or via the mouth, after which the absorption takes place in the gastrointestinal tract; rectal, or via the anus; (intra)ocular which is via the (inside) of the eye; inhalation, which can be done via smoking, vaporizing, or nebulizing; subcutaneous or transdermal, which is under or through the skin; and intramuscular, which is for example done with inoculations. During these administration modes, it is possible that some of the medicine gets lost or otherwise not administered efficiently, and that not all of the drug reaches the systemic circulation (caption and image taken with permission from TRC Pharmacology Database).

Figure 1: If a drug is given by any other route than intravenously (directly into the bloodstream), it is considered extravascular and must therefore undergo absorption into the bloodstream. Here, the bloodstream is called the “systemic circulation” and is depicted in the center of the image. The various routes of administration depicted are oral, or via the mouth, after which the absorption takes place in the gastrointestinal tract; rectal, or via the anus; (intra)ocular which is via the (inside) of the eye; inhalation, which can be done via smoking, vaporizing, or nebulizing; subcutaneous or transdermal, which is under or through the skin; and intramuscular, which is for example done with inoculations. During these administration modes, it is possible that some of the medicine gets lost or otherwise not administered efficiently, and that not all of the drug reaches the systemic circulation (caption and image taken with permission from TRC Pharmacology Database).

Factors that can affect absorption

Absorption of compounds such as THC or CBD depends on many factors such as the formulation, mode of administration, dose, concomitant use with food or other substances, and individual physiological characteristics.

7, 8, 9, 10 Since each person responds differently to the same treatment, there are two important factors to understand when considering patient treatments within the scope of administration:

Bioavailability and Inter-/Intra-variability.

Inter-individual variability is the difference in drug effects between different individuals. The same dose of the same medicine might work for you, but can be toxic to another patient. This also applies to the effectiveness, safety, and tolerance of the drugs. Factors that contribute to this variability are age, gender, weight, disease, and many others.

Intra-individual variability is the discrepancy in effects within the same person when taking the same dose of the same medicine: you might think that the same medicine always has the same effect in the same person, but this is not the case. The effect can be influenced by factors such as whether the drug is taken with or without food, the time of the day, or how a person is feeling around the time of dosing. It is important for patients to understand the reasons behind different dosing of drugs between individuals.

1. Absorption via inhalation (lungs)

With inhalation, product is absorbed via the lungs. Inhaled THC can be detected in the blood within five minutes, and the effects are typically felt within 10 minutes.

11

Smoking

Smoking is the most prevalent form of cannabis administration and gives very fast effects due to a rapid delivery of THC from the lungs to the central nervous system without the so-called first-pass metabolism (read more about it on

Metabolism page.

12, 13 The

bioavailability of THC after smoking cannabis is estimated to be between 2% and 56%, of which the upper range is relatively high.

14, 15, 16, 17 This variability of the bioavailability can be due to factors that include the inter- and intra- individual variability of smoking dynamic, such as inhalation volume, amount, duration, and spacing of puffs.

Smoked CBD absorption has been studied in fewer than 10 studies as of 2020, but not much is known about the bioavailability of this administration method. A study from 1986 in five males found an estimated mean bioavailability of 31%, with a minimum of 11% and a maximum of 45%.

18

Vaporizing

With vaporization, the volatile cannabinoids enter the system through lung absorption of the vapor. The

bioavailability of vaping is relatively high and generally does not differ compared to smoking.

19

Watch a brief summary video on

cannabis inhalation vs. cannabis ingestion made in collaboration with

Enlighten on

YouTube or on

the screens page.

2. Absorption via oral route

Oral cannabis products are often called edibles. With oral administration, a compound is swallowed through the mouth, goes down the digestive system and gets absorbed in the small intestine. Via the intestine, the drug makes its way to the liver and enters the central blood (systemic) circulation. In theory, small amounts of product could be absorbed in the oral cavity, but there is too little scientific information on this topic to draw any conclusion about how often this happens and how much might get absorbed.

Due to the longer distance that a drug needs to travel in the body, the absorption of cannabis through oral administration happens at a later time than through inhalation. After oral absorption, generally, THC and CBD can be detected in the blood after 30-60 minutes and the peak concentrations are approximately one to two hours for THC and CBD.

2, 20 Generally, the time points that people feel the strongest effects, are not long after the time that the blood concentrations of THC are the highest. For the cannabis geeks among you: the time points that people feel the strongest effects are closer to the time points that the peak concentrations of active metabolite 11-OH-THC have been reached in the blood.

2

The bioavailability of THC through the oral route is approximately 10-20%, which means that 10-20% of the parent compound eventually reaches the bloodstream.

21 The estimations on the bioavailability of oral CBD have only been done from animal data and are roughly in the same range as the bioavailability of oral THC. Due to slower absorption, which results in delayed effects, patients who are inexperienced with taking cannabis tend to overdose when taking it orally.

22 In other words, if they don’t feel any effect within the first hour, they may take more cannabis thinking that the dose wasn’t high enough, which can lead to undesirably strong effects once they start manifesting.

3. Absorption via oromucosal and sublingual route

Most sublingual cannabis products are a spray or a tincture. Tinctures are applied with a dropper. Sublingual administration means that medication is placed under (

sub, in Latin) the tongue (lingua). The absorption under the tongue happens via the abundance of blood vessels there, and a relatively thin skin.

Oromucosal (

or-,

os, which means mouth, and

mucosa, which is the skin layer that produces mucous) is an administration method that works via the mucosal skin in your mouth, including the inside of your cheeks and your gums. Although these two routes of absorption happen after putting the medicine in the mouth, they are generally not the same as the oral administration due to the different locations of absorption: sublingual and oromucosal absorption happen directly via the oral cavity, whereas oral absorption only happens later in the digestive system. This generally has different consequences for the effect onset time, the effect strength, and the effect duration. After sublingual and oromucosal absorption, the drug goes directly into the central blood (systemic) circulation, while oral absorption goes through the digestive system first.

Sublingual and oromucosal routes generally have a fast absorption, within seconds or minutes. For example, nitroglycerin, a medicine for a heart disorder, that is administered sublingually, takes about 6-7 minutes to reach the blood.

23 The rest of the unabsorbed drug is swallowed and metabolized in the liver, just like with other oral administrations.

24

Unlike other sublingual drugs such as nitroglycerin, there is no evidence from scientific studies that oromucosal or sublingual THC and CBD are absorbed faster or more efficiently than oral THC and CBD in humans. From human studies, oral administration appeared to have similar bioavailability and effects as sublingual and oromucosal intake.

2, 11, 20, 25 More studies are needed to better understand the pharmacology of sublingual THC and CBD administration.

4. Absorption through the skin

For a refresher about the difference between transdermal and topical administration, click

here.

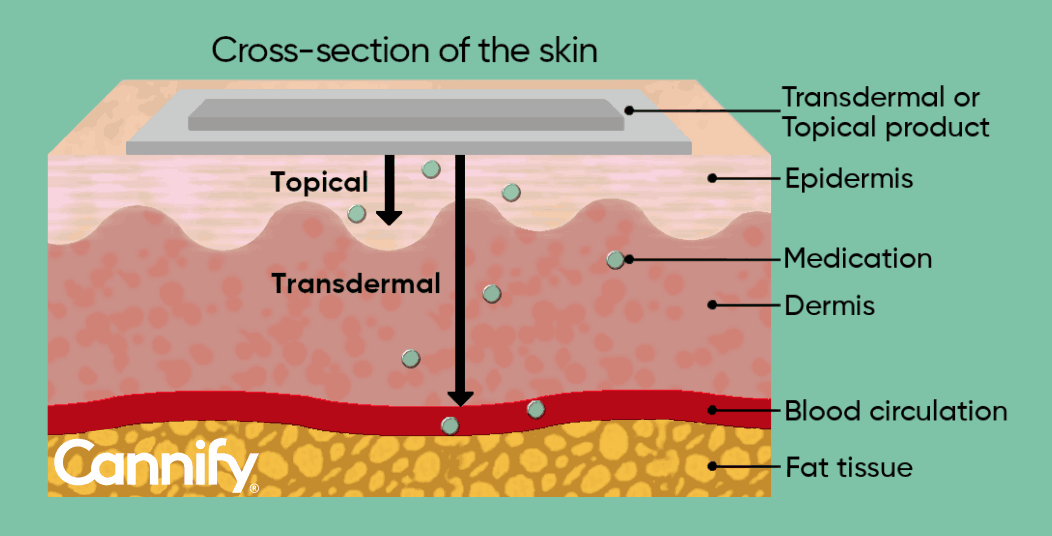

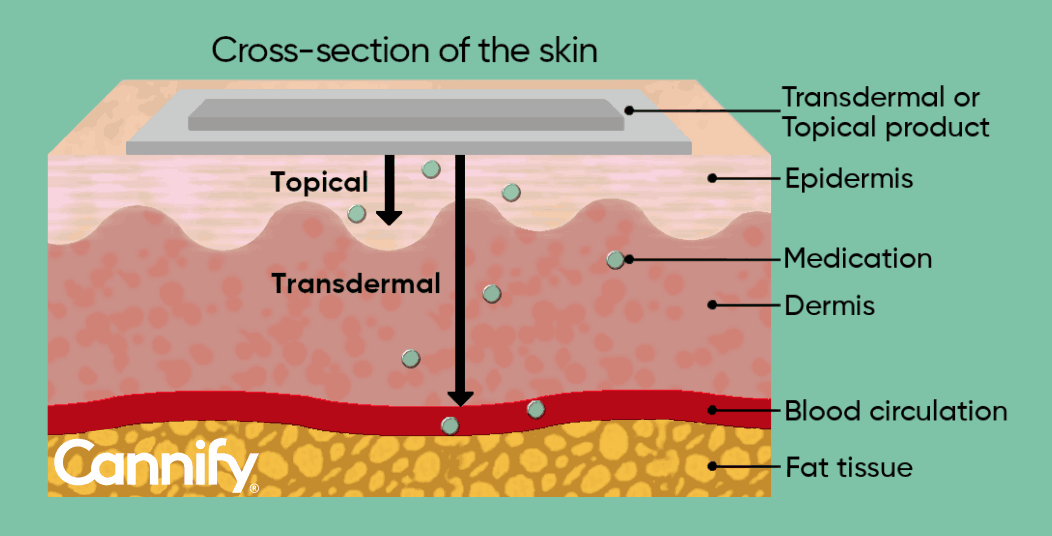

Transdermal absorption

By penetrating through the skin, drugs will reach the central blood flow.

26 The benefits of this administration method include skipping first-pass metabolism, and an easier way of administering for people who cannot or do not want to take cannabis orally.

THC and CBD are lipophilic compounds (i.e. they like fat, but water not so much). Compounds that easily penetrate skin layers, are ideally moderately lipophilic, less lipophilic than THC and CBD. Therefore,

bioavailability of cannabinoids such as THC, delta8-THC, CBD, and CBN for transdermal absorption is expected to be low when no absorption enhancer is applied.

27

There are some methods to improve absorption through the skin layers, including temperature changes, applying voltage pulses, or ultrasound. Another method is to dissolve compounds in a solution of penetration enhancers. These will increase penetration and thereby absorption by interacting with the skin’s lipids. They could be incorporated in products such as dermal patches to increase the absorption rate of THC and other cannabinoids. There are not enough studies to conclude whether THC and CBD effectively penetrate the skin for it to be of comparable effectiveness as an oral administration. Clinical trials need to be done.

Topical absorption

Topical drugs are used for local action. The word topical comes from the Greek word topikós, which means local. With a local action, the drug does not penetrate deep, and cannot reach the central blood circulation. Consequently, the topical route does not imply bioavailability of drugs, and they cannot be used to treat symptoms elsewhere in the body. Topical medications typically include eye drops, nose drops, or creams to treat symptoms of for example allergies and local infections such as hay fever or eczema.

Although there are no proven disorders for which topical cannabis application can provide treatment, topical THC and CBD are popular products.

28

Figure 2: Representation of the skin cross-section showing the different levels of medicine penetration. Transdermal products penetrate epidermis and dermis and enter the blood circulation, while topical products generally do not reach layers below the epidermis.

Figure 2: Representation of the skin cross-section showing the different levels of medicine penetration. Transdermal products penetrate epidermis and dermis and enter the blood circulation, while topical products generally do not reach layers below the epidermis.

Watch a brief summary video on

Topical vs. Transdermal made in collaboration with

Enlighten on

YouTube or on

the screens page.

- Huang, S-M; Temple, R (2008). Is This the Drug or Dose for You?: Impact and Consideration of Ethnic Factors in Global Drug Development, Regulatory Review, and Clinical Practice. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 84(3), 287-294.

- Grotenhermen, Franjo (2003). Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Cannabinoids. Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics, 3(1), 3--51.

- Grotenhermen, Franjo (2003). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Cannabinoids (327--360).

- Grotenhermen, Franjo (2004). Clinical Pharmacodynamics of Cannabinoids. Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics, 4(1), 29--78.

- Grotenhermen, Franjo.; Russo, Ethan. (2002). Cannabis and cannabinoids : pharmacology, toxicology, and therapeutic potential. Haworth Integrative Healing Press.

- Stott, C. G.; White, L.; Wright, S.; Wilbraham, D.; Guy, G. W. (2013). A phase I study to assess the effect of food on the single dose bioavailability of the THC/CBD oromucosal spray. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 69(4), 825--834.

- Huestis, Marilyn A. (2007). Human cannabinoid pharmacokinetics. Chemistry and Biodiversity, 4(8), 1770--1804.

- Karschner, Erin L.; Darwin, W.; Goodwin, Robert S.; Wright, Stephen; Huestis, Marilyn A. (2011). Plasma Cannabinoid Pharmacokinetics following Controlled Oral 9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and Oromucosal Cannabis Extract Administration. Clinical Chemistry, 57(1), 66--75.

- Bruni, Natascia; Della Pepa, Carlo; Oliaro-Bosso, Simonetta; Pessione, Enrica; Gastaldi, Daniela; Dosio, Franco (2018). Cannabinoid Delivery Systems for Pain and Inflammation Treatment. Molecules, 23(10), 2478.

- Sharma, Priyamvada; Murthy, Pratima; Bharath, M. M. Srinivas (2012). Chemistry, metabolism, and toxicology of cannabis: clinical implications. Iranian journal of psychiatry, 7(4), 149--56.

- Klumpers, Linda E.; Beumer, Tim L.; van Hasselt, Johan G. C.; Lipplaa, Astrid; Karger, Lennard B.; Kleinloog, H. Daniël; Freijer, Jan I.; de Kam, Marieke L.; van Gerven, Joop M. A. (2012). Novel Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol formulation Namisol® has beneficial pharmacokinetics and promising pharmacodynamic effects. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 74(1), 42--53.

- Madras, Bertha K. (2015). Update of Cannabis and its medical use. Alcohol and drug abuse research, 5(37), 1--41.

- Baggio, Stéphanie; Studer, Joseph; Deline, Stéphane; Mohler-Kuo, Meichun; Daeppen, Jean Bernard; Gmel, Gerhard (2014). The relationship between subjective experiences during first use of tobacco and cannabis and the effect of the substance experienced first. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 16(1), 84--92.

- Agurell, S; Leander, K (1971). Stability, transfer and absorption of cannabinoid constituents of cannabis (hashish) during smoking. Acta pharmaceutica Suecica, 8(4), 391-402.

- Ohlsson, A.; Agurell, S.; Londgren, JE.; Gillespie, HK; Hollister, LE (1985). In: Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Psychoactive Drugs (75).

- Agurell, S; Halldin, M; Lindgren, J E; Ohlsson, A; Widman, M; Gillespie, H; Hollister, L (1986). Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of delta 1-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids with emphasis on man. Pharmacological reviews, 38(1), 21-43.

- Ohlsson, A.; Lindgren, J. E.; Wahlen, A.; Agurell, S.; Hollister, L. E.; Gillespie, H. K. (1982). Single dose kinetics of deuterium labelled delta-1-tetrahydrocannabinol in heavy and light cannabis users. Biomedical and Environmental Mass Spectrometry, 9(1), 6--10.

- Ohlsson, Agneta; Lindgren, Jan-Erik; Andersson, Susanne; Agurell, Stig; Gillespie, Hampton; Hollister, Leo E. (1986). Single-dose kinetics of deuterium-labelled cannabidiol in man after smoking and intravenous administration. Biological Mass Spectrometry, 13(2), 77-83.

- Abrams, D. I.; Vizoso, H. P.; Shade, S. B.; Jay, C.; Kelly, M. E.; Benowitz, N. L. (2007). Vaporization as a Smokeless Cannabis Delivery System: A Pilot Study. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 82(5), 572--578.

- Millar, Sophie A.; Stone, Nicole L.; Yates, Andrew S.; O'Sullivan, Saoirse E. (2018). A Systematic Review on the Pharmacokinetics of Cannabidiol in Humans. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 9

- Wall, M. E.; Sadler, B. M.; Brine, D.; Taylor, H.; Perez-Reyes, M. (1983). Metabolism, disposition, and kinetics of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in men and women. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics, 34(3), 352--63.

- Monte, Andrew A.; Shelton, Shelby K.; Mills, Eleanor; Saben, Jessica; Hopkinson, Andrew; Sonn, Brandon; Devivo, Michael; Chang, Tae; Fox, Jacob; Brevik, Cody; Williamson, Kayla; Abbott, Diana (2019). Acute Illness Associated With Cannabis Use, by Route of Exposure. Annals of Internal Medicine, 170(8), 531.

- Nitrostat (2010). Drug Label. Food and Drug Administration.

- Kluwer, Walters (2009). Clinical Pharmacology Made Incredibly Easy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Third edition.

- Guy, G. W.; Robson, P. J. (2003). A Phase I, Double Blind, Three-Way Crossover Study to Assess the Pharmacokinetic Profile of Cannabis Based Medicine Extract (CBME) Administered Sublingually in Variant Cannabinoid Ratios in Normal Healthy Male Volunteers (GWPK0215). Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics, 3(4), 121-152.

- Wilbur, Robert L. (2017). The Difference Between Topical and Transdermal Medications. Gensco Pharma.

- Paudel, Kalpana S.; Hammell, Dana C.; Agu, Remigius U.; Valiveti, Satyanarayana; Stinchcomb, Audra L. (2010). Cannabidiol bioavailability after nasal and transdermal application: effect of permeation enhancers. Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy, 36(9), 1088--1097.

- Headset (2020). https://insights.headset.io/.

Figure 1: If a drug is given by any other route than intravenously (directly into the bloodstream), it is considered extravascular and must therefore undergo absorption into the bloodstream. Here, the bloodstream is called the “systemic circulation” and is depicted in the center of the image. The various routes of administration depicted are oral, or via the mouth, after which the absorption takes place in the gastrointestinal tract; rectal, or via the anus; (intra)ocular which is via the (inside) of the eye; inhalation, which can be done via smoking, vaporizing, or nebulizing; subcutaneous or transdermal, which is under or through the skin; and intramuscular, which is for example done with inoculations. During these administration modes, it is possible that some of the medicine gets lost or otherwise not administered efficiently, and that not all of the drug reaches the systemic circulation (caption and image taken with permission from TRC Pharmacology Database).

Figure 1: If a drug is given by any other route than intravenously (directly into the bloodstream), it is considered extravascular and must therefore undergo absorption into the bloodstream. Here, the bloodstream is called the “systemic circulation” and is depicted in the center of the image. The various routes of administration depicted are oral, or via the mouth, after which the absorption takes place in the gastrointestinal tract; rectal, or via the anus; (intra)ocular which is via the (inside) of the eye; inhalation, which can be done via smoking, vaporizing, or nebulizing; subcutaneous or transdermal, which is under or through the skin; and intramuscular, which is for example done with inoculations. During these administration modes, it is possible that some of the medicine gets lost or otherwise not administered efficiently, and that not all of the drug reaches the systemic circulation (caption and image taken with permission from TRC Pharmacology Database).

Figure 2: Representation of the skin cross-section showing the different levels of medicine penetration. Transdermal products penetrate epidermis and dermis and enter the blood circulation, while topical products generally do not reach layers below the epidermis.

Watch a brief summary video on Topical vs. Transdermal made in collaboration with Enlighten on YouTube or on the screens page.References:

Figure 2: Representation of the skin cross-section showing the different levels of medicine penetration. Transdermal products penetrate epidermis and dermis and enter the blood circulation, while topical products generally do not reach layers below the epidermis.

Watch a brief summary video on Topical vs. Transdermal made in collaboration with Enlighten on YouTube or on the screens page.References:_logo.svg)